Jewish Heritage and Scholarship

Explore Jewish culture, scholarship, and advocacy for health and social care with deep roots.

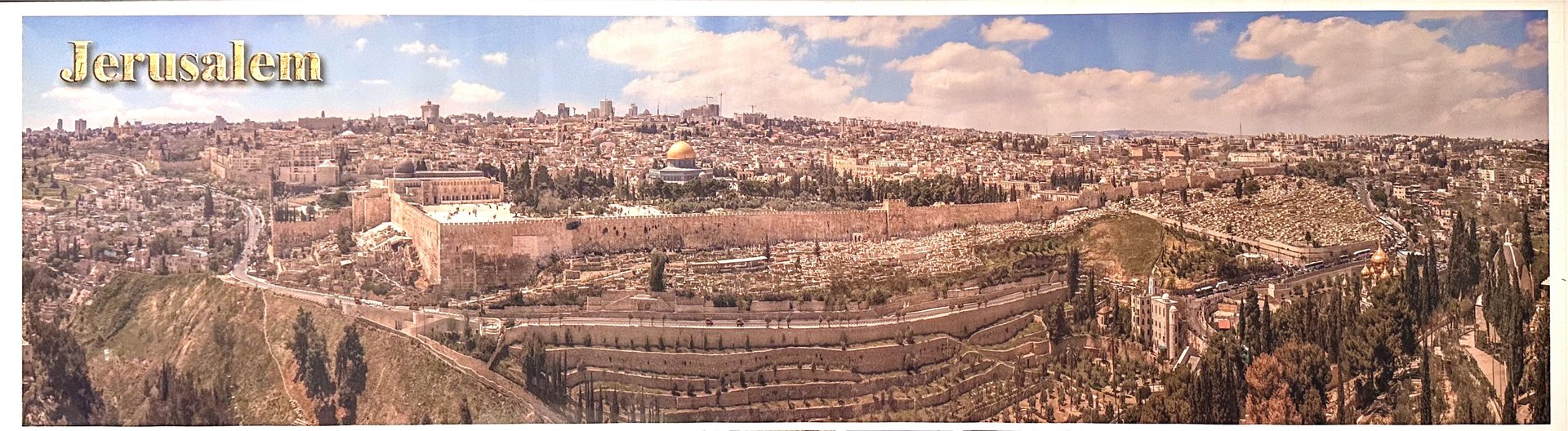

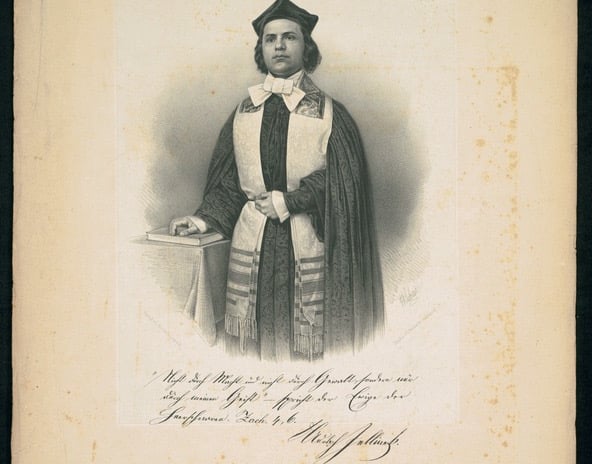

Jewish Culture and Heritage

Explore Jewish culture, scholarship, and advocacy for health and social care with deep roots.

Heritage and Wisdom in Judaism

Exploring Jewish culture, scholarship, and advocacy through the lens of a devoted husband, father, and rabbi, dedicated to preserving ancient traditions and promoting health and social care.

Community support

Jewish Scholarship Services

Providing guidance in Jewish education, genealogy, and spiritual advocacy for the community and families.

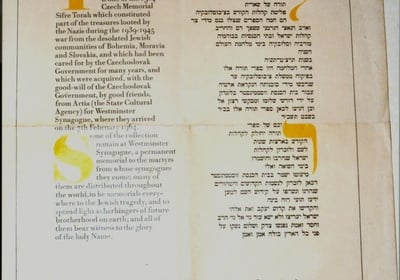

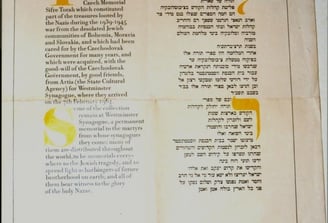

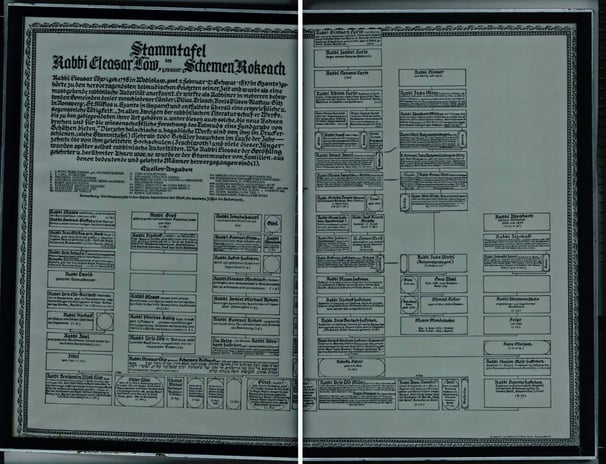

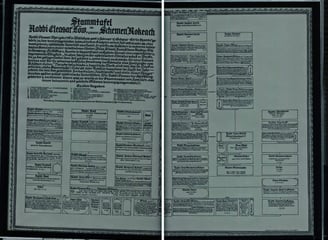

Genealogy Research

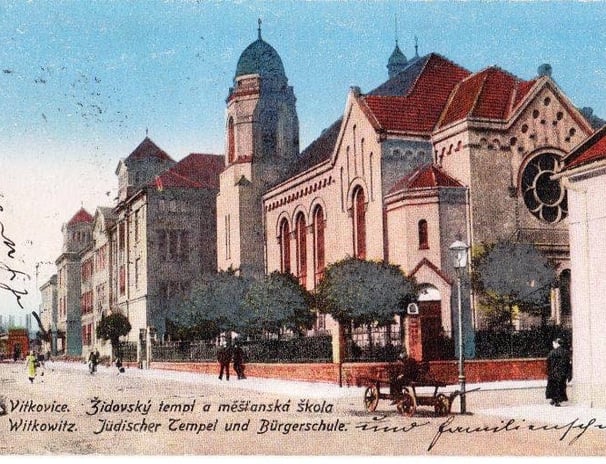

Explore your Jewish heritage with expert genealogical research and uncover your family's history and roots.

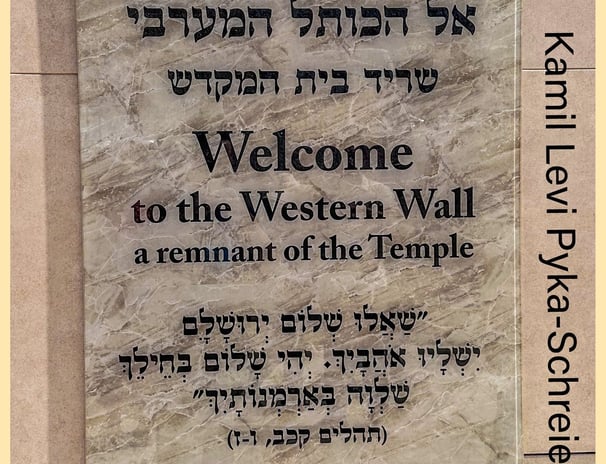

Spiritual Guidance

Receive personalized spiritual support and insights based on Talmudic teachings and Jewish traditions for daily living.

Engage in meaningful discussions on Jewish texts, traditions, and laws to enrich your spiritual journey.

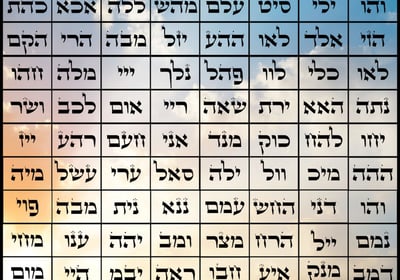

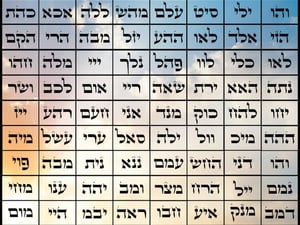

Textual Studies

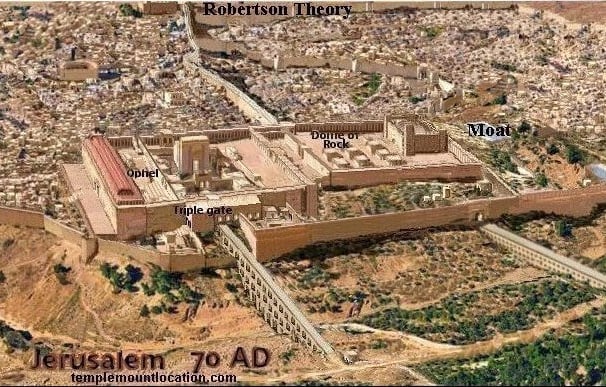

Heritage

Exploring Jewish culture, history, and spiritual wisdom through art.

Contact Us

Reach out for inquiries about Jewish education and advocacy.